‘This could be the night’: A FDNY Firefighter’s Mission to Make Museums More Equitable

At 51 years old, Fireman, Professor and Architect William F. Gates, Jr. of Brooklyn, New York, enrolled in Northeastern University’s Doctor of Education program with a clear message: space and place profoundly shape who we become. These elements influence our identity, values, worldview, and emotional resilience, often in ways we don’t fully recognize until we’ve stepped outside them. That’s why, he argues, public educational spaces like museums carry a social and ethical responsibility. The way they curate and design their environments doesn’t just display information, it teaches visitors how to see the world and can work to foster community and celebrate human commonality, or it can propagate inequity and subjugation.

The Brooklyn that Built Him

“Place shapes people”, he’ll tell you, “because it defines who they are and who they might become.” And to understand William Gates, you have to understand something about Brooklyn.

Brooklyn culture is a contradiction: gritty and warm, blunt and loyal. Outsiders might see the sarcasm, the side-eye, or the unfiltered critique and miss the deeper truth. In Brooklyn, tough love is the norm. This ethos comes from working-class, immigrant neighborhoods where community was built through action, honesty, and presence, not politeness. In that rawness lives a durable kind of love; earned, not performed.

That code runs deep in Gates: direct words, loyal heart. It’s this lens he brings to his work on “spatial segregation”, a term he invented to describe a type of redlining that can occur in public educational spaces. Gates pushes museums and public institutions to examine how their design choices convey inclusion, or exclusion. His approach, like his hometown’s, challenges to reflect and reshape, so everyone feels seen, welcomed and valued.

Family Legacy

When Gates’ father died in January 2025, it prompted a period of reflection on the man who shaped his values. The son of immigrants whose families survived the Great Irish Famine and the brutal Welsh coal mines of the early 20th century, Gates Sr. carried that legacy of resilience into his own career as a New York City firefighter, never once calling in sick. It wasn’t until a mandatory FDNY physical later in his 18th year as a Fire Captain that illness was discovered, triggering a diagnosis that forced him into retirement.

A deeply rooted tradition of labor and activism spans Gates’ lineage. His grandfather, Harold Patrick Gates, was a prominent union leader in New York City who led a large Teamster strike in 1938 at the age of 32. His father and uncle followed suit as union leaders in the FDNY, and so did his mother, a nurse and union organizer. The tradition of his family culture of social justice and resistance to the “greed ethic and obsessive materialism” he still sees permeating society today runs so deep in his family that his grandfather and uncles were interviewed in Studs Terkel’s iconic 1974 book Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do.

He recalls attending protests as young as 11, walking hand in hand with his father. “I still remember holding a sign that read, ‘Money for healthcare, not nukes,’ during the summer of 1982. We are still fighting that fight for the healthcare we deserve 42 years later.”

As a child, Gates spent weekends and summers on his grandfather’s farm in western New Jersey near the Delaware Water Gap. He also made extended trips and spent summers working on his mother’s family farm in Mississippi. This contrast between urban and rural life profoundly shaped his identity.

“Part of what contributes to the idea of my work is that I have lived this juxtapositional experience of being born in Brooklyn and growing up in NYC, where there’s this high urban density, multi-ethnic environment, being exposed to the joy of being with other people and seeing the diversity and richness; and then spending a lot of time growing up and enjoying family vacation in rural Mississippi, where my mother is from [and where her family retained a large farm], and seeing this deeply institutionally embedded racism,” Gates said.

A Gift Emerges

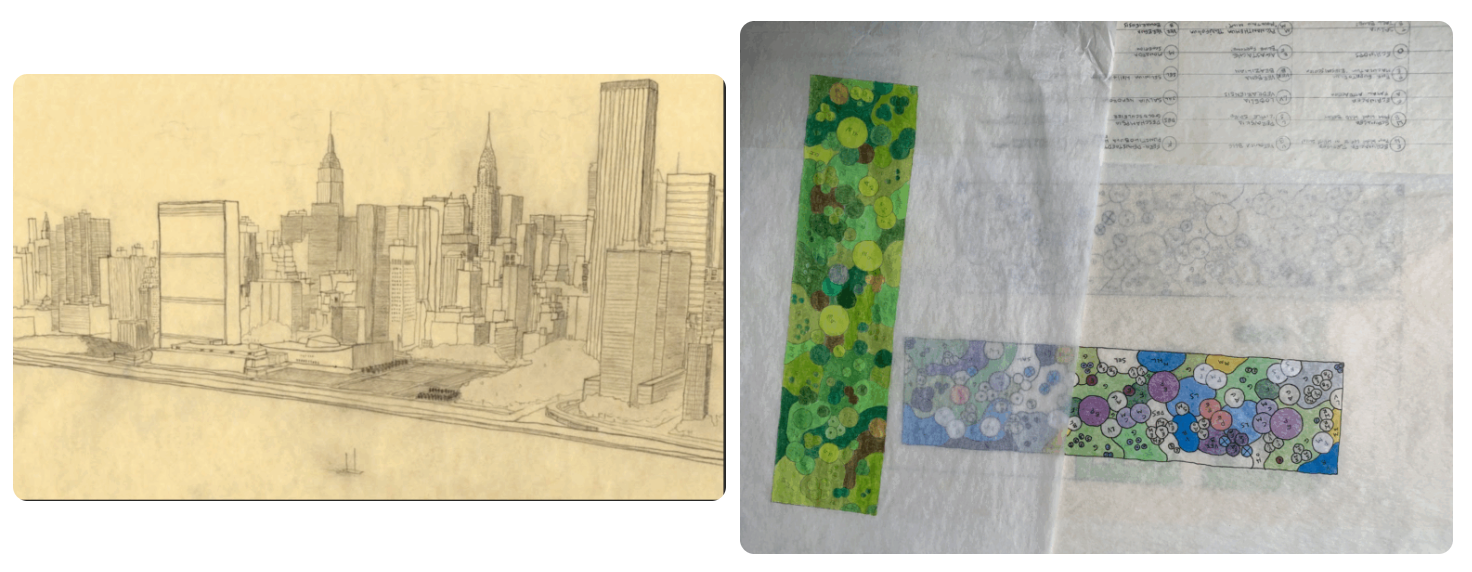

Drawn to architecture from a young age, Gates thrived in high school art and drawing classes. Encouraged by a teacher who offered to write him a recommendation for the architecture classes in his public high school, he landed a draftsman job at a New York firm by his junior year. This experience helped him get into college. During that time, his parents divorced, and his father raised four children while continuing to work as a firefighter and other jobs to make ends meet. Despite the upheaval, Gates won first place in the New York City Public Schools Scholastic Award for architectural drawing, an early recognition of his talent.

He began college at Pratt Institute in 1989, but the high tuition and long commute, two hours each way, proved unsustainable. He worked as a dishwasher and cook at a local bar to cover costs, paid in coins from a tip jar. After his first year, he transferred to the more affordable University at Buffalo, where general education requirements led him to philosophy. He discovered a deep connection between architecture and philosophical ideas and ultimately earned a bachelor’s degree in philosophy.

While in Buffalo, Gates ran a chess program for youth at the Gloria Parks Community Center, eventually being paid to continue after he tried to quit due to financial strain. He also worked as a pizza delivery driver and later a security guard in NYC. Like many philosophy grads, he struggled to find stable work. In 1996, a study abroad trip to Havana, Cuba with Professor José Buscaglia inspired him to pursue graduate studies in architecture.

At Buffalo’s School of Architecture, he fully committed to his studies. “I realized the study of architecture was really my destiny,” he said. The drive he once gave to chess and sketches now fueled his academic work.

That first year of grad school, he studied abroad again, this time in Barcelona, traveling through Europe and North Africa. “Like a chef tasting dishes, you need to see and experience great buildings to fully and deeply understand their potential for the human condition.” he said.

Encouraged by a Japanese friend, Hiroshi Iseya, Gates entered the Nisshin Kogyo Architectural Design Competition in 2001. Responding to the theme “To Live with Water,” they designed a glass aquarium-like walkway exposing polluted waters in Lake Erie. A month later, Hiroshi called; they had won first prize. Gates flew to Japan, gave interviews, his work was published and he toured architectural landmarks he’d only ever dreamed of seeing, and received a $20,000 prize.

The Other Test

As Gates neared graduation, his loyalty to the family’s firefighting legacy remained strong. In 1999, he took the FDNY entry exam, achieved a perfect score, and was ranked 308 out of 40,000 applicants. His father called with the news: he’d be in the first academy class that spring 2001. Gates asked to defer until finishing his master’s thesis, and his father agreed.

It was a familiar moment for the Gates family. Years earlier, Gates Sr. had faced a similar crossroads. A Navy All-Star with a .700 batting average, he was scouted by the Yankees and played on their farm team in Florida. But when his father, Harold Patrick, called and said, “Cut the [expletive] and get a real [expletive] job,” the dream ended. He left baseball and joined FDNY, and never looked back.

Harold, orphaned young and adopted by an aunt named Gates, never finished eighth grade but was fiercely self-taught. His resilience shaped the generations that followed.

Now, history repeated. As Gates finished his architectural thesis, his father made the same call he once received, urging his son to step into the firehouse and the family legacy.

September 11, 2001

On September 10, 2001, Gates’ brother John, a firefighter with Ladder 3 in New York City, twisted his ankle responding to a fire on 13th Street in Manhattan. He was scheduled to work the next day but called in sick.

The following morning, Gates was jolted awake by his father. They rushed to the living room and saw the Twin Towers burning live on television. His brother came running down the stairs. “He had just called the medical office to tell them, ‘I’m going full duty; I’m going to my firehouse,’” Gates recalled. He grabbed his gear and drove straight into Manhattan.

Their father didn’t hesitate either. Though retired, he gathered his equipment and headed to the World Trade Center site. On that day, he came out of retirement without a second thought.

Because Gates’ father had been with the FDNY for so long, their house became an unofficial command post. Calls poured in. “People just started calling. Wives, brothers, friends; no one could reach their loved ones,” Gates said. FEMA called too, asking specifically for his father, who had served as a captain during the 1993 World Trade Center truck bombing.

“At first, my dad thought they were calling to tell him John [Gates’ brother] had been killed,” Gates said. But instead, they asked him to report for duty. Though retired, he was part of the emergency recall, retired firefighters were being deployed to staff local firehouses as trucks poured in from New Jersey. “He told me, ‘Billy, Go downstairs and get my helmet and coat.’ And then he jumped on the Staten Island Ferry and went straight to Ground Zero.”

Everyone wanted to go to the site. Gates remembered how just days earlier, at a picnic, his friend Jay Ogren, one of the many firefighters he’d grown up around, was thrilled that Gates would soon be joining the department. “You’re gonna love it!”, Jay told him.

“Jay went missing that day. So did twelve other friends I had known my whole life,” he said. “My dad used to take me to ride in the fire trucks with them in the ’80s when I was a kid.” he said.

Back at home, the phones rang all day. Gates stayed behind to answer them. “I manned the phones and tried to reassure the callers; wives, husbands, parents, and friends. I told them, ‘It’s okay, my father and brother are there.’ And I knew it wasn’t okay,” he said.

He agreed to join the next class and was sworn in a month later.

A few days later, Gates received a call from the fire department. Because he had deferred his start; he was now at the top of the list and they were asking if he could join immediately. “There were an unknown number of firefighters dead,” he said. “I remember the words of Thoreau; [“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”] I couldn’t stand aside from the people I knew who were gone. I knew I’d regret not doing it. I knew the dangers that were coming. But I knew I had to do it.”

“I remember the words of Thoreau; [“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”] I couldn’t stand aside from the people I knew who were gone.”

Proving Himself

“Everyone thought I was crazy,” Gates recalls, “I had just earned my master’s degree in architecture and won an international award, and then I turned around and joined the fire department, right after 9/11. People asked, ‘Why would you do this, after what just happened?’”

But for Gates, the answer was clear: he wanted to serve. He was assigned to Ladder 11 on East 2nd Street in downtown Manhattan, one of the busiest companies in the city. He recalls how is father would often quote Martin Luther King Jr. when he was growing up. Reminding him that “Life’s most persistent and urgent question is, ‘What are you doing for others’”.

In his early months as a firefighter, Gates continued working at the World Trade Center exposure zone. The pile, still smoldering three months after the collapse, was a massive heap of tangled steel and ash, and it remained a place of desperate searching. Many people were still missing. Six men from his own firehouse had died that day, and his company returned regularly to help with the recovery.

“Through that winter and spring, I remember being there,” Gates said. “It was just a canyon of ruin.” He recalled the haunting stillness of those long shifts. “We had hoses stretched across the site, and I’d just watch these long arcs of water pouring into the pile,” he said. “The smoke kept rising, mixing with steam. It felt endless.”

As that first year went on, Gates began to see how deeply the built environment shaped lives, especially for those in under-resourced communities. “I saw hypodermic needles in the playgrounds and hallways, rats, people letting their dogs go to the bathroom in the elevators, stairwells and lobby’s.” he said. “It was an environment that was actively harmful, especially for children. That exposure opened my eyes to a part of humanity I might not otherwise have encountered. I’m grateful I could serve that community, even though it was emotionally and physically challenging.”

He also faced more subtle but persistent challenges, cultural ones. He entered the department as a highly educated newcomer, having pursued a graduate-level academic path that set him apart from many of his peers. “Most of the guys had come straight from high school or had been on the job for years. I was the guy with a master’s degree, and they assumed I’d be soft, even pompous”, he said.

To counter that perception, Gates made it his mission to outwork everyone. Over time, he earned not only the respect of his fellow firefighters, but their friendship. “These are bonds that last a lifetime,” he said. “We’ve stayed close. They still come and visit me. What we went through together; it was real.”

The Health Cost

When the Twin Towers collapsed, they released a cloud of pulverized concrete, glass, steel, jet fuel, electronics, asbestos, lead, mercury, dioxins, and other toxic substances. The collapse instantly transformed Lower Manhattan into a toxic wasteland. The dust was extremely fine and highly alkaline, capable of searing the airways, burrowing deep into lungs.

In the immediate chaos, many firefighters worked without proper respiratory protection. The air was thick with smoldering smoke, and the fires beneath the rubble continued to burn for months. They were all exposed to dangerous levels of contaminants.

Many developed severe respiratory conditions: chronic bronchitis, asthma, interstitial lung disease, and what came to be known as “World Trade Center cough.” Over the years, a growing number were diagnosed with gastrointestinal disorders, elevated cancer rates, and mental health conditions like PTSD and depression.

Gates was among them.

Over the years, his symptoms began subtly: at first, a blocked nostril that made it hard to breathe. Then the other side closed. Eventually, he could no longer move air freely through his nose at all. He kept it to himself, unwilling to admit something might be wrong.

It wasn’t until 2013, during his routine physical at fire department headquarters, that a physician took notice. When he examined Gates further, he immediately sent him for evaluation. The findings were serious: polyps had formed throughout his nasal cavity and sinuses, and additional tissue growth was appearing in his throat. His esophagus was also reacting; he was experiencing episodes where he couldn’t breathe and felt like he was choking. He was diagnosed with GERD, precancerous growths, and chronic airway inflammation, all traced back to his prolonged exposure at Ground Zero.

That same year, Gates was told he could no longer serve on the front lines. He was officially classified as medically disabled.

There’s no Heroes on Wall Street

For any firefighter injured in the line of duty, retirement becomes an immediate option. But Gates wasn’t ready to hang up his gear. He tried to stay on, accepting desk jobs at the department while grappling with the emotional weight of his new reality.

“It was such a big part of my life, and to leave it was traumatic,” he said. “I stayed for two more years, but I wasn’t doing what I loved. Making a difference for others, being there when they really need you, is the best thing. I remember my uncle telling me ‘There’s no heroes on Wall Street.’ Being a firefighter is the best thing there is. He was right.”

Gates had long called the firehouse “a sacred fortress of goodness.” When he was reassigned off the front line, he said, “it no longer felt like the same place.”

The timing was especially painful. “Like Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule, I had just reached that threshold after 12 years in the department, so finally, I knew what I was doing,” he said. “I was studying to take the lieutenant’s exam, just like my father had. I passed that test; it’s a beast, more than 10,000 pages of material. And I did it. But I never got to serve in that role.”

Gates retired in 2015 and in 2016 he decided to get himself and his family out of the city and focus on teaching.

A New Reality, a New State and a Union

After retiring from the fire department, he and his family moved north, settling in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 2017. He began teaching at Mount Ida College, but in early 2018, UMass Amherst absorbed the school, and Gates found himself out of a job. He began searching for teaching roles in architecture.

In 2021, Gates divorced and was granted full custody of his three children. Then in 2022, he began teaching at Boston Architectural College. Alarmed by how little the adjunct professors were paid there, and the inequity between the compensation for leadership and faculty, he launched an Instagram page to build community among the faculty and soon started organizing for a union.

“I learned a lot,” Gates said. “It’s easy to scare and divide people when they’re just trying to hold on, but raising standards in any community is a battle.”

Though he had support, not enough faculty submitted their cards, and the college eventually cut his class.

Northeastern University and a Transformative Class

Gates began his doctorate in education at Northeastern University in fall of 2022. Initially, he was interested in how artificial intelligence would influence architectural education.

The direction of his research changed in summer 2023, when he took a social justice course with Dr. Noor Ali. Around the same time, he read The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein, which exposed how government-led housing policies, like redlining, engineered racial segregation in the U.S.

He began connecting those systemic patterns to public spaces, especially education-related buildings like schools and museums. On a class field trip to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, he noticed how art was spatially segregated, African art was tucked away in dimly lit galleries on lower levels with low ceilings , while European art was displayed prominently in well-lit, expansive rooms on the upper levels of the museum with a generous allocation of space afforded to the art being displayed. The inequity in design felt intentional, and it struck a nerve.

“This work felt deeply personal,” he said. “I connected to it through different parts of my life. From the spatial divisions and dirt roads of rural Mississippi to the public housing projects on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, the inequity and subjugation was real.”

He wants to heighten awareness of spatial segregation so that children have an equitable experience in public educational spaces. He said, “My work talks to how we can use museums as essential spaces for our society.”

He quotes a Mark Twain saying: “‘That travel is fatal to bigotry, prejudice and narrow-mindedness…’ With 87 million Americans living at or near the poverty level, few have the opportunity to travel. But Museums can offer us a glimpse, a unique way to be transported to different places and times in human history to feel the work of artists and the children that walk these halls and galleries need spaces that reflect the aspirations and promises of our society.”

Currently raising his three children full-time while pursuing his doctorate, Gates also teaches “Architectural Physics” at a high school in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts. He has published academic papers on AI in architectural education and continues developing his spatial segregation research.

The weight of a firefighter’s past, the clarity of philosophical inquiry, and a Brooklyn-born commitment to justice is all carried by Gates. His work on spatial segregation is not just academic, it’s personal, forged in the grit of collapsed towers, shaped by the legacy of a father who never called in sick, and driven by the belief that the built environment reflects the values we choose to uphold. For Gates, the future isn’t just something we study, it’s something we build, block by block, with conscience and care.

In the FDNY there is a saying that every firefighter knows: ‘This could be the night.’ It is a reminder that at any moment, on any day, they might be called upon to answer the greatest challenge of their career and their lives. And because of that, they must always be ready. The challenges for Gates are different now but are no less urgent, and he is ready for them.

“Museums need to be more cognizant of their responsibility in crafting spaces and experiences and in how their architectures might continue to propagate racial segregation.”